Table of Contents

As you know, computers operate in binary code so, naturally, different kinds of symbols that we use need to be transformed into numbers. For this purpose, different encodings were created and implemented over the years.

One of the earliest was the ASCII encoding. It’s a 7-bit encoding that contains 128 (2^727) symbols based on the English alphabet. It wasn’t perfect for everyone for several reasons. First, computers started to use 8-bit sequences, bytes, for storing information and ASCII strings had extra memory that wasn’t being used. Second and most important, 128 symbols just wasn’t enough for everyone, not even for the English script itself. There was a clear need for new, improved encodings and many of them started to appear after ASCII. There were extensions of ASCII (like ISO 8859-1) or encodings for specific scripts (for example, Windows-1251 for Cyrillic). However, in different encodings, the same number could represent different symbols and that would complicate communications. The solution to all these problems had to be a unified system and that is when Unicode comes in.

What is Unicode?

Unicode is a standard for encoding and representing text. It is not an encoding per se since it doesn’t determine how symbols are converted to bytes. It is simply a specification that defines the mapping between symbols and numbers.

The Unicode Standard was proposed in 1991 by the Unicode Consortium. As the name suggests, Unicode was intended as a universal standard and it’s safe to say that now it is.

Unicode can also be viewed as an extension of the ASCII table: in fact, the first 128 numbers in the Unicode represent ASCII symbols. All in all, Unicode can accommodate 1,112,064 code points, but as of May 2019, only 137,994 are occupied. The fact that most code points aren’t designated yet is also one of Unicode’s advantages. It means that for years and years to come, we can add new letters, scripts, punctuation marks, and pictograms to the standard without running out of space.

How does Unicode look?

Unicode consists of two parts: Universal character set, UCS, and Universal transformation format, UTF.

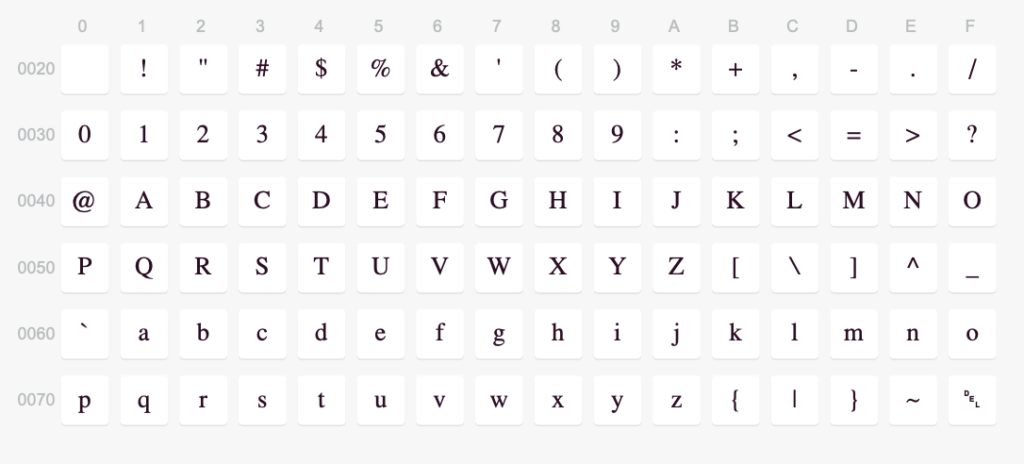

UCS is essentially an index of all symbols supported by the Unicode and codes for those symbols. Let’s take a look at a segment of this index. This is a part of Basic Latin, the symbols that have traveled from ASCII:

In Unicode, every symbol corresponds to a number—code point. A code point is usually presented with U+ followed by its hexadecimal value. The hexadecimal number in the code has from 4 to 6 digits depending on its place in the standard. For example, the code for the Latin Capital Letter Q is U+0051. By looking at the table, you can see that Q is at the intersection of row 0050 and column 1 which is where the code number comes from. Most Unicode codes can be easily transformed into HTML codes: you just need to convert the hexadecimal number to decimal and write it in an HTML format. The HTML code for the letter Q is then Q. You can check if hexadecimal 51 equals decimal 81.

Unicode code points are divided into 17 planes with numbers from 0 to 16. Each plane is a continuous group of 65 536 (2^{16}216) code points. The plane with the number 0 is called Basic Multilingual Plane (BMP) and it contains characters for most modern writing systems and languages as well as many symbols. They have codes from U+0000 to U+FFFF. The ASCII part of the BMP includes the first 128 characters, from U+0000 to U+007F.

The rest of the planes (1 through 16) are called “supplementary planes”. Most of the supplementary planes are unassigned and empty which leaves room for additions.

The Supplementary Multilingual Plane (SMP) (codes from U+10000 to U+1FFFF) is the next plane after BMP. It includes many historic scripts and, what is quite interesting, special characters and symbols. SMP has musical notations, alchemical symbols, geometric shapes, and even emojis! If your favorite programming language supports Unicode strings, chances are you can put emojis or other interesting characters in your strings!

Unicode Implementation

We’ve already mentioned that along with UCS Unicode has UTF — Universal transformation format. UTF is a set of encodings that support Unicode. Encodings describe how symbols (or, rather, their code points) are transformed into bytes according to a particular character set and vice versa. There are several UTF encodings, but the most popular are UTF-8 and UTF-16.

UTF-8 is the most commonly used encoding in the world as around 94% of the Internet is encoded in UTF-8. UTF-8 uses from 1 to 4 bytes per code point and is capable of representing all code points of the Unicode. UTF-8 is also backward compatible with ASCII. UTF-16 is similar and the difference between the two is mostly technical. You could use UTF-16, of course, but we recommend sticking to UTF-8 like most of the Internet.

Summary

In this topic, we’ve covered Unicode — a standard for encoding different kinds of symbols. Unicode itself is not an encoding, it doesn’t define how characters are converted into bytes for computers to understand. What it does, is it defines a Universal character set — a mapping between symbols and hexadecimal numbers, code points. Code points are divided into planes, among which the most important is the Basic Multilingual Plane (BMP).

Unicode also provides several encodings within the Universal transformation format (UTF). UTF-8, an encoding that supports the entire Unicode, is the predominant encoding of the Internet.

Unicode is everywhere. The page you’re reading right now uses the Unicode Standard to display this text. Since you’ll have to work with texts in some way or another, it’s important to know what Unicode is (and what it isn’t). Understanding the standard and its relation to the most common encodings can help you solve or altogether avoid encoding/decoding errors.

U+0043 U+0068 U+0065 U+0065 U+0072 U+0073 U+0021